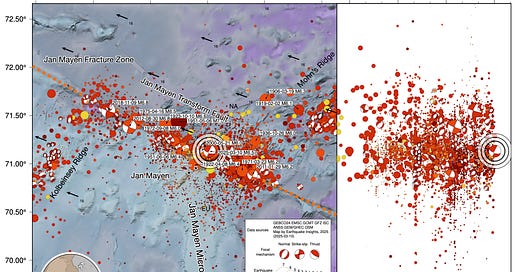

M6.5 earthquake strikes remote Norwegian island

We look at the fascinating setting of this event

Citation: Hubbard, J. and Bradley, K., 2025. M6.5 earthquake strikes remote Norwegian island. Earthquake Insights, https://doi.org/10.62481/ae435c11

Earthquake Insights is an ad-free newsletter written by two independent earthquake scientists. Our posts are written for a general audience, with some advanced science thrown in! To get these posts delivered…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Earthquake Insights to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.