Rebuilding Historic Urban Areas after Disasters

An interview with Dr. Patrick Daly

Citation: Daly, P., Hubbard, J. and Bradley, K., 2023. Rebuilding Historic Urban Areas after Disasters. Earthquake Insights, https://doi.org/10.62481/45509ccb

The recent earthquakes in Morocco, Turkey, and Syria caused extensive damage and loss of life, and also destroyed many ancient monuments and historic urban neighborhoods. We turned to our friend and colleague, Dr. Patrick Daly, who studies the aftermath of disasters, to discuss some of the unique challenges faced when trying to rebuild historic areas after disasters. Patrick is an archaeologist/environmental anthropologist at the Earth Observatory of Singapore (EOS), Nanyang Technological University. He has studied post-disaster reconstruction following the 2004 Indian Ocean Tsunami and the 2015 Nepal earthquakes.

We asked Patrick to draw on his experiences to comment on some of the unique challenges of rebuilding historic urban areas. We hope that his answers provide some insights to people impacted by the recent disastrous earthquakes in Morocco, Turkey, and Syria, as well as to organizations trying to have a positive influence on reconstruction and recovery.

What is your experience studying post-disaster reconstruction?

I have directed several large studies of post-disaster recovery following the 2004 earthquake and tsunami in Aceh, Indonesia and the 2015 earthquakes in Nepal. I spent years on the ground in disaster zones, working with and learning from a wide range of people, from disaster-affected persons to government officials and NGO workers.

One of my areas of interest is how our cultural heritage contributes to our resilience in the face of environmental stress. I have conducted research about how local inhabitants react to the loss of cultural heritage caused by disasters and how cultural sensitivity can be part of reconstruction policies.

The recent earthquakes in Morocco, Turkey, and Syria caused a lot of damage, especially to older, traditional buildings. How does your experience relate to this?

It is easy to see parallels between the damage to cultural heritage in Morocco, Turkey, and Syria and what happened in Nepal following the 2015 earthquakes. I visited some of the historic neighborhoods in Morocco and Syria well before the earthquakes, so I have a personal sense of what was there and what was lost.

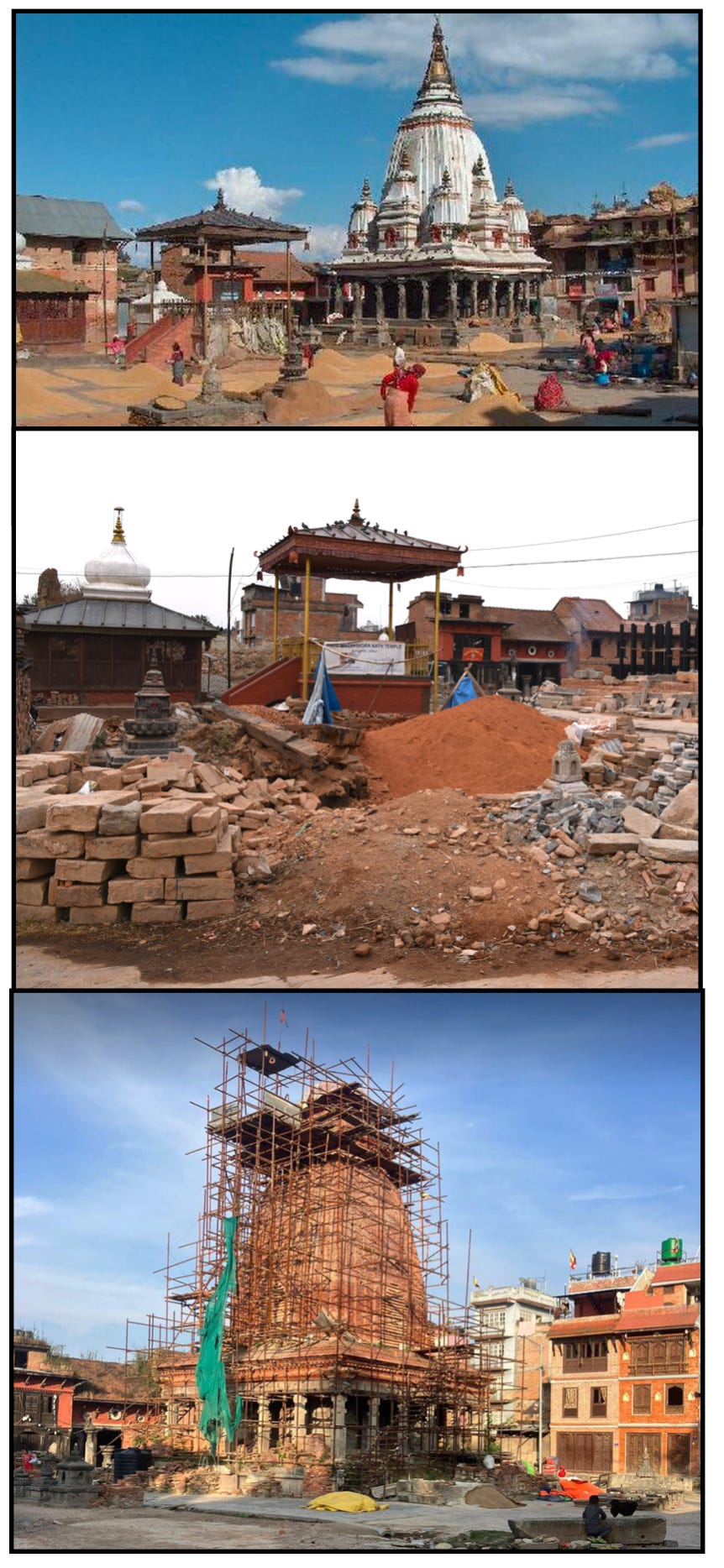

One of the first things that struck me when I started working in Nepal after the earthquake was the extensive damage to the temples, museums, and heritage sites. Seeing monumental sites that had stood for centuries destroyed really drove home the power of the earthquake. I’m pretty sure that people in Morocco, Turkey, and Syria were just as shocked and dismayed at the damage to their cultural heritage as people in Nepal. I suspect that many of the same conversations about how to rebuild historic sites are occurring now. Hopefully some of what we learned in Nepal will contribute to these discussions.

Are there lessons from your experiences in Nepal that you feel are relevant to these other countries?

Some of the general lessons that we learned in Nepal that might be relevant to any historic urban areas which are hit by a major disaster:

First, the recent earthquakes reinforce that cultural heritage sites are victims of disasters. Dozens of major historic sites and landmarks suffered significant damage, including prominent national heritage sites such as the Old City/Medina (a UNESCO World Heritage Site) and Kutubiyya Mosque in Marrakech, Morocco; the famous Tinmal mosque in the Atlas Mountains, Morocco; the ancient Citadel in Aleppo, Syria, and the Gaziantep Castle in Turkey. Given the deep and rich histories of those areas, I am sure that a full list of damaged heritage sites would be extensive. This represents a profound loss of both local and globally important heritage.

Second, rebuilding urban areas after disasters is always complex, expensive, and emotional – and even more complicated when dealing with culturally important areas. It is almost always easier, quicker, and more cost effective to clear out heavily damaged areas and rebuild using contemporary construction techniques and materials. It takes considerably more effort, skills, special materials, and costs to integrate heritage preservation into a major post-disaster reconstruction project.

Third, heritage is more than just prominent monuments. The media tends to focus on damage to iconic structures. But the extensive tracts of private traditional houses and commercial buildings that make up historic urban neighborhoods are also important parts of the cultural heritage.

Finally, post-disaster reconstruction can have a huge impact on cultural heritage. The decisions of local residents and aid actors about how to balance post-disaster priorities (disaster risk reduction, modernizing and upgrading infrastructure, the aspirations of individual families and communities) and allocate scarce resources largely determine the shape of post-disaster cultural heritage.

Why are cultural and historic sites so important?

I first went into post-disaster situations with the preconceived idea that the loss of cultural heritage matters, and that carefully restoring cultural sites would be an agreed upon priority for both residents and aid actors. I quickly learned this was not always the case!

In early 2006 I partnered with a local heritage NGO to conduct a survey of cultural sites in Banda Aceh damaged by the tsunami. I expected to see the extensive damage caused by the tsunami, but I was surprised to see how much additional damage was being caused by the reconstruction. I have a lasting memory of seeing piles of beautiful and elaborately carved gravestones from the 16 – 19th centuries C.E. left on the side of the road, half buried in mud in the intertidal zone, or deliberately removed and stacked in piles by construction workers building new houses. It was an early and discouraging lesson that not everyone valued those old gravestones the same way that I did! Frankly, in complex humanitarian emergencies, the fate of old buildings and gravestones is usually far down the priority list for both aid organizations and local residents.

So why does it matter? Why should additional resources be allocated to heritage when disaster zones are filled with seemingly more urgent issues?

First, cultural heritage is an integral part of our history and identity. Losing important cultural sites due to disasters or conflict can be destabilizing and even traumatic, especially for marginalized communities who are already struggling to maintain their identities in the face of rapid development or discrimination.

Second, cultural buildings often serve as venues for practical community functions such as meetings and education. In emergency situations, members of the community often gravitate toward such places to locate family members, get information from trusted sources, and receive or distribute assistance. Losing such facilities can make it more difficult for people to participate in the reconstruction process.

Third, traditional places can be important for psycho-social recovery. For example, places of worship can be important for communal grieving. In the first several months after the tsunami in Aceh, surviving mosques played a number of critical roles for both the practical needs of rebuilding and in providing stability, comfort, and hope for people who had lost everything. Reestablishing traditional landmarks can be seen by local residents as a benchmark for recovery and progress.

Finally, historic sites and districts are popular tourist attractions. Historic city centers like the Medina in Marrakech or Patan in Nepal commonly contain guesthouses, restaurants and cafes, museums, and shops for traditional arts and handicrafts. The loss or transformation of such areas can have negative economic impacts and permanently displace or eliminate traditional livelihoods.

When cultural sites were damaged by the earthquakes in Nepal, what kinds of organizations assisted in the recovery, and what happened?

Almost immediately after the earthquake, images of destroyed cultural sites showed up on the news. A combination of the Nepali government, foreign governments, international NGOs (i.e. UNESCO), foreign national heritage actors (i.e. Archaeological Survey of India), academics, and private donors supported the repair, restoration, or complete reconstruction of many of the most prominent communal heritage sites. Repairing or restoring prominent heritage sites was a high-profile form of bilateral assistance, with foreign governments and other donors ‘adopting’ damaged sites in Nepal and providing funding and technical support for restoration efforts.

However, rebuilding the large tracts of private traditional houses that gave many of Kathmandu’s old neighborhoods their character was a lot more challenging. Many of the aid actors interested and equipped to support rebuilding communal heritage sites did not have the resources, capacity, or mandate to build private houses. Further, the Nepal Government limited the amount of funding that could be donated to help individual families rebuild their houses to about $3,000 USD, because they wanted to make sure aid was equally distributed to all disaster victims. While this amount was generally sufficient to rebuild a single-story family home in a rural area, it was not nearly enough to rebuild a multi-story traditional house in an urban area.

Many different levels of official government agencies (national, municipal, neighborhood, etc.) were involved in setting reconstruction policy – a process that evolved over the course of the first year after the earthquakes, culminating with the creation of a National Reconstruction Agency. While that was going on, a wide range of national and international aid actors got involved in making rebuilding plans for villages and neighborhoods. Finally, residents formed their own community reconstruction committees. This led to many different visions for how to rebuild historic neighborhoods. These plans often elicited support from local communities, but we found that very few were accompanied by the resources needed.

What kinds of laws and guidelines were established to manage rebuilding in Kathmandu?

In Nepal’s historic neighborhoods, much of the damage and loss of life occurred when traditional buildings collapsed. While some of these structures had stood for centuries, it is likely that long periods of neglect and lack of regular maintenance weakened load-bearing walls, which caused catastrophic damage – much worse than in structures built with modern steel reinforced concrete columns. While some people advocated for rebuilding using traditional techniques, there was a general consensus that safety from future earthquakes should be the main reconstruction priority.

Thus, right from the start, safety was the main priority for most stakeholders involved in rebuilding. We found a strong consensus from top government officials and international donors down to disaster-affected residents that new buildings needed to be safe from future earthquakes. This resulted in official guidelines based on disaster risk reduction priorities. For example, post-earthquake building codes focused on increasing seismic resistance through the use of steel-reinforced concrete frames, capping the height of residential buildings in urban neighborhoods, requiring minimum plot sizes for buildings, and widening streets and alleys.

While all of these aligned with engineering best-practices, many of the specifics were incompatible with the built environment in historic urban areas. This led to tensions between residents who valued heritage preservation and government agencies. This eventually resulted in new, modified guidelines specifically for historic neighborhoods, which mandated modern construction techniques for structures, but allowed, and in some cases insisted on, the incorporation of distinctive heritage features on building exteriors/facades.

How did residents approach rebuilding in Kathmandu, and how did this affect historic houses?

Money was THE major consideration. Conserving, repairing, or rebuilding urban areas using traditional architectural styles, construction techniques, and/or construction materials was much more expensive than rebuilding using ‘modern’ techniques, by some estimates by between 30% and 40%. Many residents who would have preferred a traditional house, or a house with at least some traditional elements, simply could not afford it. In some neighborhoods, all residents were required to rebuild using traditional features. There we found that many people struggled financially because of the additional costs, and often had to sell ancestral land or go into substantial debt.

Sometimes the logistical problems went beyond cost: rebuilding or restoring using traditional materials and techniques requires access to skills and materials that might no longer be readily available. Furthermore, some residents found it difficult to get the timber needed to build door and window frames and the ornate balconies typical of traditional houses – either because of cost or because of environmental protection laws banning the harvest of hardwood.

What were the main outcomes in Nepal?

For cultural monuments, in most cases the exteriors accurately reflected pre-disaster aesthetics, while the underlying structures were strengthened with steel-reinforced concrete. This process was generally completed within two to four years after the earthquake. Rebuilding communal heritage sites went relatively smoothly, with many of the outcomes seen as satisfactory by residents. While sometimes messy, I would consider the rebuilding of such heritage sites as a success story.

Within our case study neighborhoods in Nepal, there was a major reduction in traditional-style housing after reconstruction. Almost none of the post-earthquake houses were built using traditional architecture and materials. Most post-reconstruction ‘traditional’ style houses were effectively modern structures with steel-reinforced concrete frames that adhered to building codes, with exterior facades that drew on traditional aesthetics. Many old, traditional houses have been replaced with new houses lacking any traditional components.

The neighborhoods where the community prioritized heritage restoration to attract tourists generally ended up with many more new houses that looked traditional. In other neighborhoods, heritage restoration was generally a function of household wealth, with a small number of very nicely built traditional-style houses built by rich families, mixed in with modern or fairly nondescript brick houses.

This shift away from traditional houses had social impacts. Large, multi-generational families were often split up because building codes did not allow sufficient space. Many residents were bothered by the 3.5-story limit on building height and restrictions on incorporating usable outdoor space on the upper levels. People lost spaces needed to work from home and exterior terrace spaces used for drying crops.

How long did reconstruction take?

Most people were not able to start building for at least the first year as it took a while for the government to release new building codes. Residents also waited to see how much funding would be provided by the government and donors (answer – not much). From the second year on, the process of rebuilding was largely determined by household wealth and support from NGOs. If all funding and paperwork was in order, including government approval of building plans, it generally took less than a year to rebuild a multi-story house. However, most families took longer, with people moving into finished or partially finished houses between two to five years after the earthquake.

What were some of the unexpected challenges that might be relevant to Morocco, Turkey, and Syria?

In Nepal, many people found it difficult to access assistance, secure bank loans, and get building permits because they were not able to prove formal land ownership. Land tenure was a patchwork of formal ‘modern’ private land ownership, customary land tenure, and informal understandings between extended families – many people did not have deeds or titles. This was a huge problem for both the government and NGOs trying to help with housing.

It was also common for extended households to live within the same building, which was constructed incrementally based on evolving family size, composition, and needs. The earthquake and rebuilding exposed and exacerbated a lot of pent up family drama by forcing people to make decisions under stress. It was amazing how often we were told that people had yet to rebuild because of seemingly intractable conflicts between siblings about what seemed to us to be relatively minor issues. Donors and NGOs wanted to provide individual homes for nuclear families, which is often not appropriate when dealing with historic urban areas.

In addition, most historic urban areas are the result of generations of construction. Tourists in Kathmandu might simply see lots of beautiful old buildings, but those neighborhoods include many different styles of construction from different time periods. This is part of what gives texture and nuance to historic urban areas. In Nepal, the official heritage restoration by-laws provided a limited menu of what ‘heritage’ features should be included within new traditional-style houses. This forced people to conform to a rather arbitrary and homogenous aesthetic. In some cases, local residents told us that they were not allowed to recycle parts of their destroyed houses, such as antique wooden door and window frames, because they did not conform to the new official ‘heritage’ standards.

What do organizations interested in helping rebuild historic sites and neighborhoods in Morocco and Turkey need to hear, based on your experiences?

Prioritize any communal cultural sites that could support both practical reconstruction efforts and the recovery of disaster-affected persons. Given that almost the entire population of Morocco is Muslim (at least officially), repairing or rebuilding historic mosques and other religious structures could check a lot of boxes. In Aceh, there was a massive outpouring of financial and technical support from across the Muslim world – and especially from the rich Gulf states – to help rebuild mosques, prayer halls and community centers.

Work with local residents to determine how to rebuild historic neighborhoods from the earliest stage of reconstruction. A patchwork reconstruction, mixing traditional and non-traditional approaches, can drastically change the entire aesthetic and long-term safety of an area. However, the higher the level of restoration, the more expensive and difficult it will be to achieve. If stakeholders are motivated to restore traditional houses, aid actors will need to find ways to subsidize rebuilding without causing tensions with other disaster victims who do not live in traditional houses or historic neighborhoods. This can be accomplished by providing technical expertise (engineers, heritage architects, etc.), subsidizing building materials, or providing special low- or no-interest loans for rebuilding heritage houses. If communities are able to attract funding to help them rebuild traditional houses, then it doesn’t make sense for the government or NGOs to place caps on individual donations in the name of equity.

Do not over-promise. People affected by disaster need clear and trusted information about what comes next, what the government and aid agencies are going to provide, and what they (local residents) need to manage on their own. In Nepal, many residents in historic urban areas mapped out plans at the household level for rebuilding but then waited for several years before rebuilding. Many of these households might have started and finished their houses much sooner and experienced less stress if they were not waiting for help that ultimately did not arrive. It is very important to avoid causing additional trauma because of the failure of government agencies, NGOs, and insurance companies to provide the support that was promised or anticipated. It can be very damaging for people if the reconstruction is defined by years of frustration, inaction, perceived betrayal, and feeling marginalized.

What do people in Morocco who were impacted by the earthquake need to know, and how can they best access the help they need?

First, things will take time to rebuild – especially if you want to do it well. It is likely that even if things are very efficient, it could take two to five years before most houses are repaired and destroyed houses replaced. The next few years will be hard. Things will almost certainly get better for most people, but there will also be large numbers of victims whose struggles will be prolonged – and who might end up leaving.

It is important for people affected by disaster to be present and involved in whatever capacity they can while their homes are being rebuilt. This can be active participation in the planning, working on the construction, regular supervision, etc. This can lead to higher quality of construction and more customization of the space to family needs and comfort. It can also help with recovery from trauma, and help residents learn about construction, disaster risk reduction principles and techniques, and their history and culture.

Is there anything people in other seismically active areas containing historic sites and neighborhoods should be doing now to mitigate future impacts? Are there ways to access funds before, rather than after, disasters to make historic sites less vulnerable?

Conduct detailed structural surveys of important communal sites. Assess the physical vulnerability of structures to the widest possible range of earthquakes or other disasters that are likely to occur in the area. If there are structural issues, then heritage management plans should factor in how to best retrofit such places, or at the least develop safety and evacuation protocols in case of a disaster. I would like to see UNCESO or other major international heritage organizations supporting such efforts more proactively rather than waiting for a tragic event.

Develop formal guidelines for maintaining historic structures and regular inspections to ensure that they remain structurally sound. In Nepal, one of the major causes of damage to traditional housing was the lack of maintenance and regular repair of house walls. Over decades or longer, mortar eroded out and walls sagged and bulged. It is possible if that those buildings had been better maintained, the overall damage and death toll would have been lower.

Collect and store detailed architectural and structural data from important sites so that IF they are damaged or destroyed, it is easier to repair or rebuild. These can include traditional architectural plans, historic and recent photos, and detailed 3d point clouds generated from photogrammetry and LiDAR.

Dr. Patrick Daly is an archaeologist/environmental anthropologist at the Earth Observatory of Singapore (EOS), Nanyang Technological University. Feel free to leave comments below; we will pass them on to him!

References:

Daly, P., Barenstein, J.D., Hollenbach, P. and Ninglekhu, S., 2017. Post-disaster housing reconstruction in urban areas in Nepal. IIED, London. https://www.iied.org/sites/default/files/pdfs/migrate/10836IIED.pdf

Daly, P., Ninglekhu, S., Hollenbach, P., Duyne Barenstein, J. and Nguyen, D., 2017. Situating local stakeholders within national disaster governance structures: rebuilding urban neighbourhoods following the 2015 Nepal earthquake. Environment and urbanization, 29(2), pp.403-424. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956247817721403

Very informatiive, and hopefully the suggestions will be taken into account by the relevant authorities. Also, interviews of other scholars expands upon the already useful information provided in Earthquake Insights.