M4.7 earthquake rattles southern Texas

Earthquakes in this area are linked to fluid extraction - including a M4.8 in 2011

Citation: Hubbard, J. and Bradley, K., 2024. M4.7 earthquake rattles southern Texas. Earthquake Insights, https://doi.org/10.62481/b8604b13

A magnitude 4.7 earthquake shook southern Texas just after midnight on February 17th, 2024 (06:32 UTC). The earthquake was weakly felt in both San Antonio (~ 70 km to the NW) and Austin (~130 km to the NNE). Locally, a seismometer recorded acceleration of 18% g (the acceleration due to gravity), representing strong shaking (intensity VI). More than 400 people reported feeling the earthquake to the USGS; if you live in the area, consider submitting your own report.

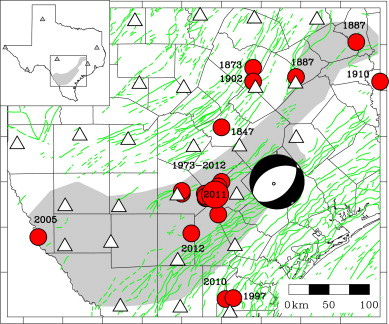

The earthquake occurred within a band of seismicity that has been notably active since ~2010. A magnitude 4.8 earthquake occurred here in 2011, drawing some attention. That event appears very similar to the recent M4.7, both in its location and its type - a normal-mechanism earthquake, on a fault oriented northeast-southwest. Both the 2021 and more recent 2024 earthquakes occurred near the southwestern tip of a ~120-km-long linear band of earthquakes. More diffuse seismicity has been detected across a broad region to the southwest.

A study examining the relationship between seismicity and oil and gas activities concluded that the 2011 M4.8 Fashing earthquake, and other earthquakes that occurred in the vicinity starting in 1973, were almost certainly induced by oil and gas activity. Although most induced earthquakes in the United States are thought to be linked to wastewater injection into the subsurface, the 2011 earthquake - and an earlier period of seismic activity from 1973-1993 - appear to have been associated with extraction of oil and water.

These earthquakes occurred within the Eagle Ford region, where gas and oil is being actively extracted from both Mesozoic limestones and (via hydrofracking) the Eagle Ford Shale. These rocks are cut through by a set of northeast-southwest trending faults that seem to be reactivating due to anthropogenic activity. Most of these faults were likely never tectonic. Instead, they probably formed as part of salt-related deformation: thick layers of salt in the subsurface migrated as they were squished by overlying rock. Now, these same faults are shifting in small earthquakes due to anthropogenic activities.

Since 2011, seismic activity in the region has only increased. We note that the seismic network seems to have improved starting in 2019, allowing the detection of as small or smaller than M2 (dark blue on the histogram above). When comparing the rate of seismicity, it is important to compare apples to apples (earthquakes within the same magnitude band). Earthquakes above M3 (yellow/orange on the histogram above) have been consistently identified since 1980, and show a clear increase in frequency since ~2018. Perhaps that increase led to the installation of more seismometers.

One interesting aspect of the recent M4.7 is that it was preceded by foreshock activity: a M4.4 twelve minutes before the mainshock, and before that a M3.9 almost three hours prior to the mainshock. Other, smaller events were also detected, but it is difficult to distinguish them from the background. Most earthquakes do not have foreshocks, but they are not uncommon. Foreshocks are simply smaller earthquakes that occur before larger ones; they cannot be identified as precursory behavior as the vast majority of smaller earthquakes do not trigger larger ones.

In natural settings, foreshock triggering is often interpreted as simply the result of stress changes on nearby faults. In this setting, where fluids pressures are implicated in the generation of seismicity, it seems possible that the foreshocks and mainshock are linked more directly by fluids. Presumably this earthquake will be followed by investigation of the injection and extraction processes at nearby wells, to understand the links between these events.

Although the largest earthquake recorded so far in this region has been a magnitude 4.8, people in the area should be aware that larger earthquakes are possible.

References

Frohlich, C. and Brunt, M., 2013. Two-year survey of earthquakes and injection/production wells in the Eagle Ford Shale, Texas, prior to the Mw4. 8 20 October 2011 earthquake. Earth and Planetary Science Letters, 379, pp.56-63. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.epsl.2013.07.025

Frohlich, C., DeShon, H., Stump, B., Hayward, C., Hornbach, M. and Walter, J.I., 2016. A historical review of induced earthquakes in Texas. Seismological Research Letters, 87(4), pp.1022-1038. https://doi.org/10.1785/0220160016