Deadly M6.1 earthquake strikes western China

Thrust earthquake accommodates oblique compression in northeastern Tibetan Plateau

Citation: Hubbard, J. and Bradley, K., 2023. Deadly M6.1 earthquake strikes western China. Earthquake Insights, https://doi.org/10.62481/a1759ed1

要阅读这篇文章的中文版,请点击此处(由 Google 自动翻译)。

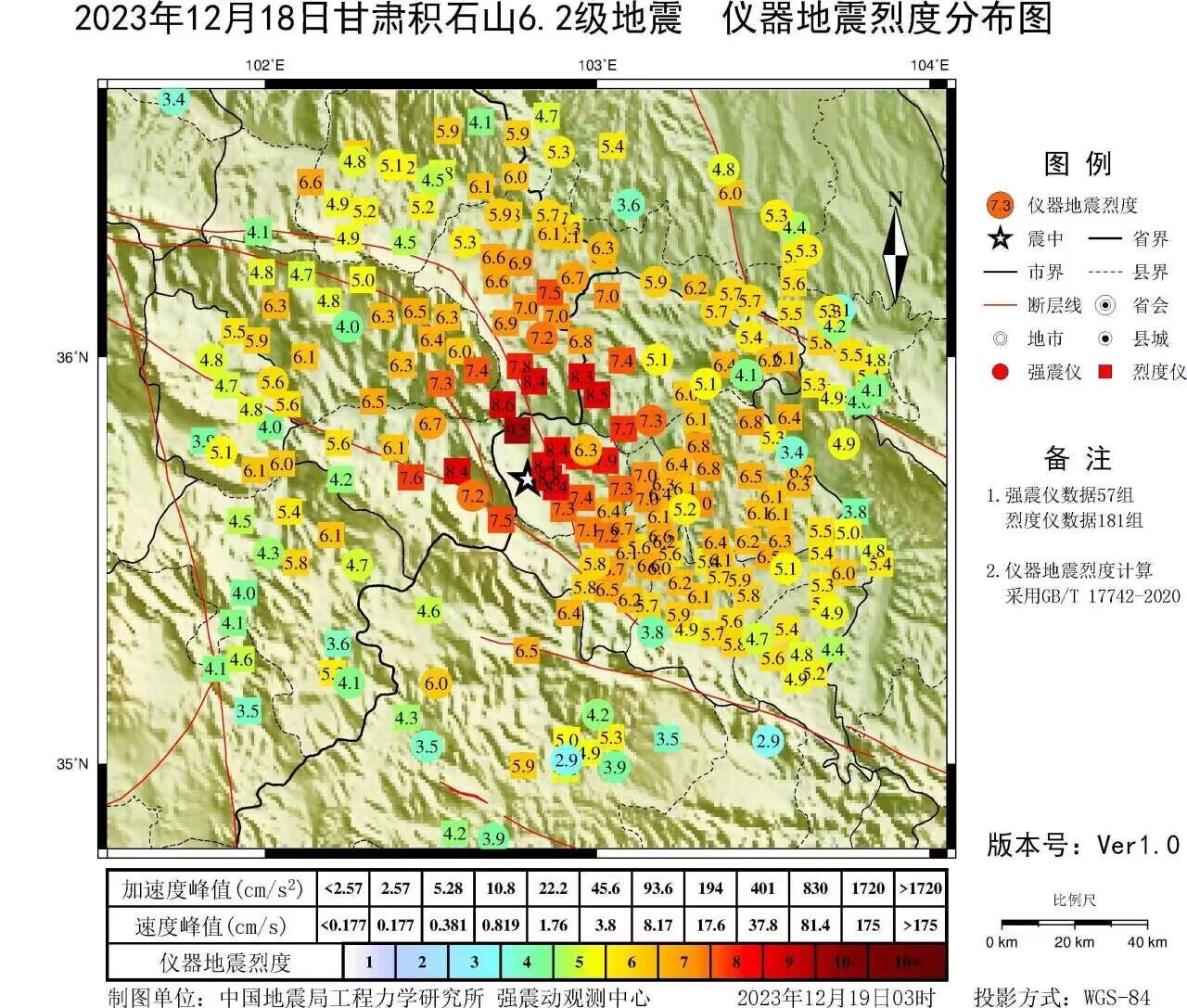

A magnitude 6.1 earthquake struck western China at 23:59 local time on December 18, 2023, near the border between Gansu and Qinghai Provinces. The earthquake, which occurred at shallow depths, caused shaking of intensity VIII (severe) near the epicenter; over 10 million likely experienced at least intensity IV (light) shaking, including the city of Lanzhou.

Reuters reports that more than 155,000 homes in Gansu were either damaged or destroyed and at least 100 people were killed. In addition to damage to homes, the earthquake triggered landslides and damaged roads and infrastructure. Because the earthquake occurred at night during a cold snap, residents now face a choice between exposure to cold or occupation of potentially dangerous structures that may be further damaged by aftershocks or triggered earthquakes.

Reuters quoted an old man as saying: “I've lived for more than 80 years and had never seen such a big earthquake.” Indeed, no equivalently large earthquake has been recorded in the area during that time. However, if you extend the timescale back a further ten years, the record shows a larger event: a magnitude 6.9 in 1936. This is a reminder that earthquake timescales can be very long - with hundreds or even thousands of years between large events.

Tectonic setting

The earthquake occurred in the northeastern part of the Tibetan Plateau - a vast uplifted region thousands of kilometers in all directions. This tectonic feature, built by fifty million years of collision between the Indian and Eurasian Plates, is linked to earthquakes all across the region. The deadly M7.9 Wenchuan earthquake in 2008 was caused by slip on the Longmenshan fault, on the eastern border of the plateau, where it is bordered by the low and flat Sichuan basin. Almost 2,000 kilometers away, the M7.8 Gorkah earthquake in Nepal was caused by slip on the Main Himalayan Thrust, on its southern border. Both of these events were thrust earthquakes, reflecting convergence between the blocks on either side.

While the southern and eastern borders of the plateau are sharp topographic features, other areas - like the northeast and southeast - are more distributed. These areas are cut by many faults, most of them strike-slip faults that accommodate the extrusion of crustal blocks sideways, away from the zone of continental collision. The active faults in these areas have also caused large earthquakes, including M7.5+ earthquakes in 1920, 1927, 1947, and 2021 (as shown on the map below). The impacts of these events varied dramatically depending on the specific location. For instance, the 2021 earthquake occurred within the high, mostly unpopulated plateau, and caused limited damage; the same is not true of the 1920 and 1927 earthquakes to the northeast (more on that later).

The map above includes green arrows. These are GPS vectors; each one represents the movement of the crust at that location relative to stable Eurasia. The arrows show that the crust in the southwestern part of the map is moving ~20 mm/yr east compared to Eurasia; this movement decreases progressively from southwest to northeast. The vectors are mostly not parallel to the mapped faults (black lines): while the arrows point east with a little bit of north, the faults are mostly oriented ESE. This misalignment yields transpression: the faults must accommodate a combination of strike-slip and thrust movement.

In transpressive settings, that combination of two types of slip can occur in two ways: either faults can slip obliquely - neither strike-slip nor thrust, but at an angle that includes both - or the slip can be partitioned - both thrust and strike-slip faults develop, and they divide the slip up between them. The focal mechanisms on the map above show that there is some slip partitioning happening, with some earthquakes nearly pure strike-slip and other nearly pure thrust. There are also some oblique-slip earthquakes on the map.

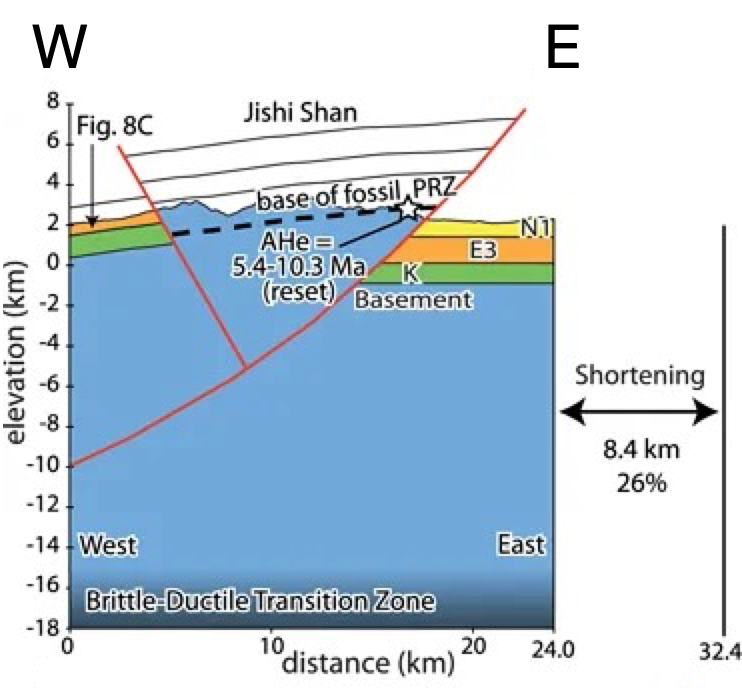

The December 18 earthquake was primarily thrust, with a component of oblique slip. It occurred near a small mountain range known as the Jishi Shan, which is oriented NNW-SSE, roughly perpendicular to the convergence direction between northeastern Tibet and Eurasia.

The Jishi Shan is bounded by thrust faults that match the orientation of the earthquake focal mechanism. While the location of the earthquake places it just to the east of the range, location uncertainties suggest that the best fault match for this earthquake is probably the eastern range-bounding fault.

Hazard in the Loess Plateau

In the northeastern part of the Tibetan Plateau, earthquakes pose a special hazard. This is an area known as the Loess Plateau - a region where thick deposits of wind-blown dust, or loess, have accumulated. These thick layers of loess have naturally compacted, allowing them to be excavated to build traditional earthquake homes called yaodongs. Most people in rural parts of the Loess Plateau continue to live in and around yaodongs.

Unfortunately, while yaodongs are comparatively inexpensive and well insulated, they are not resilient to earthquake shaking. The 1927 M7.6 Gulang earthquake killed more than 40,000 people; the 1920 M8.0 Haiyuan earthquake killed more than 250,000. In both cases, much of the devastation was linked to widespead collapse of loess caves. In fact, the deadliest earthquake ever recorded - the 1556 Shaanxi earthquake - occurred in the Loess Plateau; this event may have killed up to 830,000 people due to the combination of direct impact, famine, and plague.

The Reuters report for the recent M6.1 earthquake that 155,000 homes were damaged or destroyed indicates that indeed, homes in this area are not resilient to earthquakes. With limited information so far, the level of damage remains unclear, and we do not know if the damaged homes are yaodongs or another form of construction - Reuters describes them as “mud houses,” built from “earth and clay.”

After a magnitude 6.1 earthquake, we expect significant aftershock activity to persist for weeks to months. Homes and buildings which sustained damage, but did not collapse during the M6.1 event, may now be vulnerable to smaller magnitude aftershocks. Finally, the probability of an even larger earthquake occurring in the area is also higher now than before, due to changes in stress on nearby faults.

References:

Lease, R.O., Burbank, D.W., Zhang, H., Liu, J. and Yuan, D., 2012. Cenozoic shortening budget for the northeastern edge of the Tibetan Plateau: Is lower crustal flow necessary?. Tectonics, 31(3). https://doi.org/10.1029/2011TC003066

Zhao, X., Xue, J., Zhang, F., Han, J., Du, J. and Hu, X., 2022. Energy capacity and seismic resistance of loess cave structures under field ground motions. Journal of Building Engineering, 45, p.103473. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jobe.2021.103473